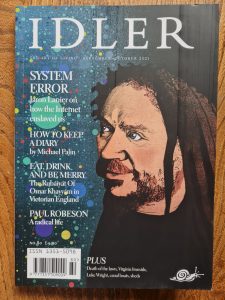

My Philosophy column in the new Idler, September-October 2021.

There is an old tradition of writing against figures or groups you disagree with. “Against” is the operative word. Augustine wrote “Contra Faustum”, which was a riposte to the Manichaean, Faustus. Thomas Aquinas wrote “Contra Gentiles”, which was a defence of Christianity against Judaism and Islam, with which Christianity has an uncomfortable amount in common.

My contra would be against a certain type of Christianity that is doing the rounds amongst the chattering classes right now. The title would be: Against Moral Christianity.

Those who are for moral Christianity make a case like this. First, they describe the ancient Greek and Roman worlds as dark and depraved. Slaves? They built on the suffering. Punishment? Crucifixions by the thousand. Foreigners? They called them barbarians and built walls to keep them out.

Then, Christianity arrived. At its centre is the figure of a man, Jesus, strung up on one of those shameful, agonising crosses. During his life, he taught people to love their neighbour, be a good Samaritan and, perhaps most shockingly of all, love enemies. A seed was sown that, in time, grew into the rights and freedoms which we take for granted. The modern world owes much to Christianity and we are fools to turn our backs on it.

Oddly enough, it is not just Christians making this case. The prominent agnostic historian, Tom Holland, is championing the cause, with the added twist that atheists who presume they have freed themselves from superstitious nonsense are really Christians in disguise.

Take the culture war tweets from anthropologist and atheist Alice Roberts, who is president of the campaign group, Humanists UK. “Humanism isn’t a religion,” she asserts as if a creed. “Religions are irrational.”

Atheists think that they are distancing themselves from God as they chuckle, but their preoccupation is Christian through and through, the argument goes. Christianity stressed orthodoxy, made windows into people’s souls, burnt heretics at the stake, and brought pogroms into the world. Culture wars? They’re thoroughly religious in spirit.

In contra epistles, there comes a point at which the author, having outlined, more or less fairly, some of the beliefs of their opponents, subtly turns against them. That moment is now.

Stakes and pogroms? Heresy trials and culture wars? Is Christianity really better than what came before? In his magisterial doorstopper, A History of Christianity, Diarmaid MacCulloch points out that as soon as Christianity became the official religion of the Roman empire, Christians started persecuting one another. The first recorded case of intra-Christian harassment comes within two years of Christianity’s public acceptance. It’s a doubly troubling fact because that was easily within living memory of by far the severest Roman persecution, under Diocletian. So much for loving your neighbour.

And what about loving your enemies? It wasn’t a new idea, in fact. Socrates argued for it, according to Plato. “We ought neither to requite wrong with wrong nor to do evil to anyone, no matter what they may have done to us,” the gadfly of Athens concludes in the dialogue called Crito, a case that is repeated in the Republic: “For it has been made clear to us that in no case is it just to harm anyone.”

I am genuinely baffled that decorated scholars, as well as popular historians, don’t seem to know this. I can only think that they are caught in a moral panic that makes them forgetful. Or could it be something else – that not many Christian leaders really understand Jesus’s teaching.

Now, hold on a minute, you may be thinking, your columnist is going too far. However, I am only repeating what one prominent teacher of the faith admits in a recent book on Jesus’s parables. The one about the Good Samaritan is clear enough, so it seems. But when you look more closely, it turns out that most of Jesus’s parables are amoral or immoral. They feature unjust judges, unforgiving servants, and labourers who get the same pay regardless of how long they have worked. It’s not social justice, so what was Jesus on about?

What doesn’t occur to the apologists is that Christianity might not be about morality. After all, there was plenty of it around in the first century. The Jews read the Hebrew Bible with its prophetic calls for justice. The Stoics majored on how to live, as did the Epicureans, though they were a little less successful in terms of impact. Nietzsche picked up on that in an interesting way. He liked the Epicureans because they seemed to him to resist what he called the “slave morality” of Christianity. What the German disliked about Christianity, as he saw it, is the way it turns human weakness on its head, by valorising it, rather than attempting what the Epicureans did. They strove to overcome weakness with practices that strengthen resolve – in Epicurus’s case, an ability to face suffering and death with equanimity.

Jesus was born into the moral melee of the ancient world and, I think, realised something else. If the world really is to change, people need a radical revolution of heart that makes life look utterly transformed. Centuries of moralism had shown that route doesn’t cut it.

This means that the parables aren’t finger-wagging tales that have a “palpable design” on you, as T.S. Eliot noted. They are koans designed to interrupt pretty obvious assumptions. They are riddles that might open eyes to see, and ears to hear, something completely different.

I echo Monty Python’s famous catchphrase. It was part of their genius that they knew more about religion than many priests and prelates. Recall the 16-ton weight scenes, when a massive mass falls on someone when they least expect it. My guess is that meeting Jesus would have been like that. He was out for conversion, not nudging you to improve your behaviour.

September 2021 marks the 700th anniversary of the death of Dante, whose Divine Comedy is one of the greatest expressions of Christianity. (Plugs can appear in contra diatribes, so let me add that my new book is out this month too – Dante’s Divine Comedy: A Guide For The Spiritual Journey.) It is striking that Dante sees souls who are hung up on morality in the Inferno. They are so obsessed with right and wrong, fearing that they sinned or raging because they were sinned against, that they have become stuck. That’s the problem with morality. It offers guidance but mostly delivers guilt.

What Christianity initially taught was something far more radical, so much so that I suspect most Christian teachers today are afraid to say it. Their forebears weren’t. “The Word of God became a man so that from a man you might learn how to become a god,” wrote Clement of Alexandria in the second century. “By dwelling in one, the Word dwelt in all,” affirmed Cyril of Alexandria in the third century. “The Son of God became man so that we might become God,” added Athanasius of Alexandria in the fourth. “The descent of God to the human level was at the same time the ascent of humanity to the divine level,” preached Leo the Great in the fifth.

Dante has that experience of ascent. He describes it in the Paradiso. He knows himself to be spinning “with the love that moves the sun and the other stars”.

Nowadays, it would be called nondualism. You might hear more about it from someone who has taken psychedelics than a bishop in a purple shirt. It’s an astonishing image of ourselves and we need it. Morality merely condemns. The spiritual vision of true religion jolts us into knowing we are alive.