This essay is published by Beshara Magazine.

The pandemic is said to have exposed modern society to its vulnerabilities. Nowhere is this exposure clearer than in relation to death. Covid has revealed that, nowadays, most people have inadequate ways of relating to this fact of life. The weakness is doubly striking as wisdom and religious traditions insist that death is not an unfortunate end to life or the bleak absolute that makes limited life meaningful. Rather, death is the pathway to eternal life, and dying before you die is the central task of mortal existence.

William Blake (1757–1827) lived in the period during which western culture’s uncoupling from death took hold. Across the course of his work, and particularly in his epic poems, The Four Zoas, Milton and Jerusalem: The Emanation of the Giant Albion, he developed a fourfold perceptual schema that illuminates the depth of vision which has been lost, as well as offering a path back to its recovery. That journey begins by recognising the unhelpful conceptions that we might have about death. The first of these is what he called ‘eternal death’, which is the impression that death has the final word on life. This kind of death is experienced in the state of mind Blake called ‘Ulro’, where it is treated as pretty much meaningless, and people’s demise is barely even sad. Their passing is reduced to the recording of statistics, prompting panic in response to what seems like a meaningless litany of death that only knows of bleak loss and dark voids.

Luckily for us, it is impossible to live in Ulro because ultimately we are not numbers on charts. Within the panic occuring in Ulro is a desire for more, and from it a second worldview will emerge. Blake called it ‘Generation’ because it recognises that death is part of life – though only in the sense that mortality marks the end of a life and the passage of the ongoing generations. This kind of death is, therefore, treated as an affront and a travesty; it is theorised as unnecessary. Hence in a technological culture, which confuses mechanical movement with the soul’s vitality, the indefinite delay of death, and dreams of overcoming it, becomes an orientating goal. The upshot is that Ulro’s panic is replaced by manic consumption during the short years that people take to be their lot.

However, this new desperation can itself prompt the emergence of a third attitude towards death, which Blake said was characteristic of another worldview he called ‘Beulah’. Here death is seen not as a travesty but a tragedy. The loss of loved ones and the suffering endured fosters feelings of compassion and love. Death is surrounded by the desire to care and comfort, mourn and commemorate. Moods of panic and mania yield to a steady, melancholic presence. Death is known to be intensely meaningful, though the full extent of its significance remains beyond the horizon of perception. People hope that there’s more and they believe in an afterlife. But they do not know of immortality.

The possibility of the hereafter feeds, in turn, a yearning that finds fulfilment if the lack leads to a fourth awareness, which is also an awakening. Blake called it ‘Eden’ or ‘Eternity’. Now, physical death is known to have an asymmetric relationship to life. It is not the last word but, rather, holds a surprise. People depart but they do not cease to be. It becomes clear that life contains death much as a labyrinth contains turnings. Death invites a step into the unknown and the embrace of uncertainty because that is the route to the centre.

However, Blake also knew that becoming established in Eternity is not gained by the application of reason or the seductions of metaphor. Death itself is the way to know the all. So he devised ways to undergo ‘dying before you die’ in his verse and art. Like the mystery religions of premodern times, that journey starts by confronting the fear of eternal death.

Eternal Death and Eternal Life

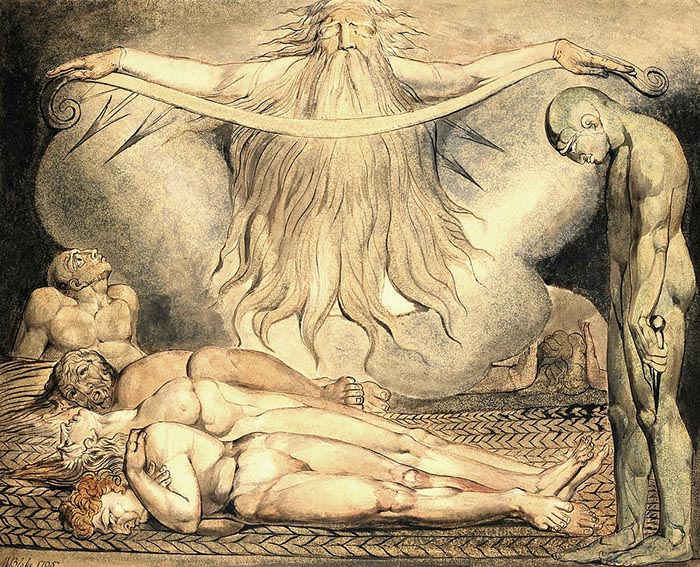

Consider Blake’s print, The House of Death. It depicts the suffering of five poor individuals. They have the plague and lie on mat beds, curled up or racked in pain. At their feet stands a man. His head is bowed, his skin grey. He holds a knife. He is the figure of despair, his dagger is a dart of death. With it, he taunts the dying. It’s a grim scene.

Now, look again. Another presence dominates the image: an old man with a long white beard. He is enthroned on clouds and, between outstretched arms, unrolls a long scroll. Beneath it shoot vicious darts. He’s a divine figure, a patriarchal god. And he’s preoccupied. Although he hovers right over the suffering individuals, he doesn’t see them; he doesn’t care to see them. His eyes are resolutely closed.

This is eternal death. It is not just about suffering. It is not only marked by misery and grief, poverty and pestilence, though it contains those tortures for sure. It is really the workings of a mental system that can grip souls and a society.

To contemplate The House of Death is to see into the experience of life when ruled by Urizen, the god of Ulro. All appears mechanical and bound by the material. Urizen, whose spirit invades those who live under him, scorns what is not demonstrated by reason and empirical evidence. Everything looks inert, best treated as lifeless objects, which is why Urizen doesn’t see the people beneath him. He has what Blake called ‘single vision’ and it is deadly: it destroys life because it does not know what life or death are.

Now consider a second image.

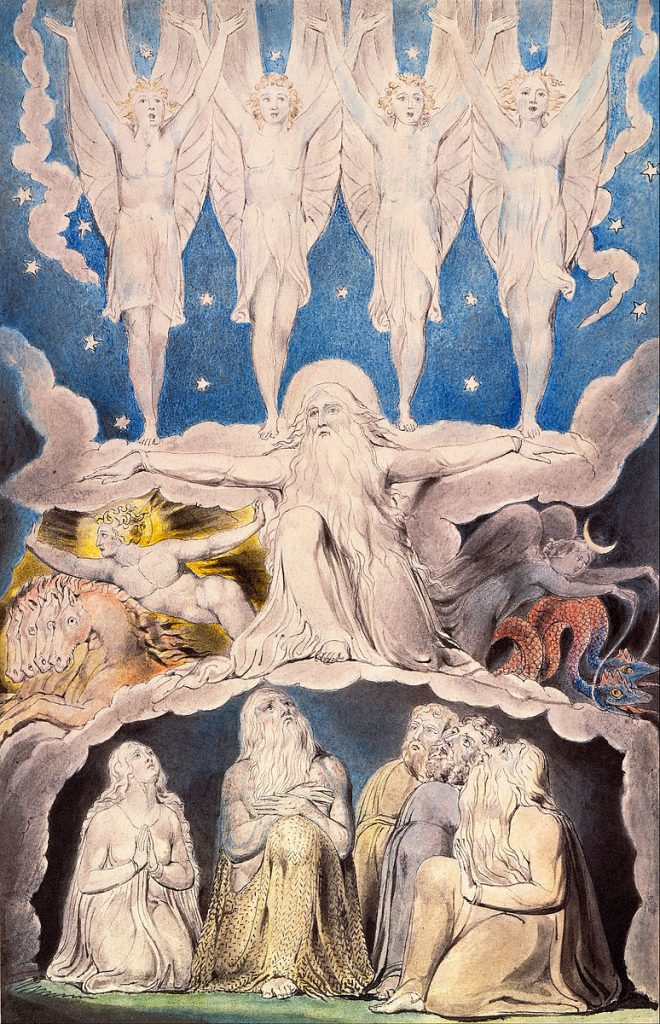

It, too, features five human individuals at the bottom of the picture, but they are looking up. They are sitting in what looks like a cave, though the rock is really ephemeral cloud and so they can see through its ceiling, in wonder. Above them, through the cloud, they can see another bearded man. He’s a divine figure, once more, though, interestingly, he looks remarkably similar to the man directly beneath him. His arms are outstretched like Urizen’s were, only now, his eyes are open. They are in touch with distant horizons, which is perhaps why he does not unroll a scroll, but unleashes cosmic energy.

Under his right arm is Helios, the sun god who keeps time by riding a golden chariot across the sky. Under his left arm is Helios’ sister, Selene, the moon god. She rides a silver chariot powered by serpents, which stand for vital, lively experience. Above the divine figure is a third section. In it, angels dance with upstretched arms which Blake explains in the verse beneath the image. They are the morning stars who delight with awareness of Eternity. We see four of them, though in other versions of the image, more arms at the edge of the picture suggest they continue to infinity.

The print is one of the best known from Blake’s series retelling the story of Job. The scene comes towards the end of the Biblical story, when God reveals his awesome creativity to Job because Job kept his faith in the divine vision. ‘Canst thou bind the sweet influences of Pleiades or loose the bands of Orion,’ Blake has inscribed above his picture, adding below, ‘When the morning Stars sang together. & all the Sons of God shouted for joy’. The sequence had begun with Job assuming his upright piety was blessed. But God grants Satan’s wish: ‘All that he [Job] has is in thy power’, God says, prompting Satan to unleash death in Job’s life. ‘Behold there came a great wind from the wilderness and smote upon the four faces of the house and it fell upon the young men and they are dead’, Blake inscribes on the scene of destruction. Death appears to rule Job’s life.

Blake interprets the story as a revelation. Job knows grievous death and yet comes to see life in all its fullness. With sight of eternal life, existence is experienced not as the callous manifestation of an oppressive system, but as a continually unfolding dynamic of creativity. Around the margins of the picture, in other versions of the image, Blake charts the scenes of creation, from ‘Let there be Light’ to “Let the Waters bring forth abundantly.” These were not moments in history. They are the very qualities of eternity in time.

Another way of putting it is that this is an image held within the presence of Jesus. The central figure in Christianity, whom Blake also calls ‘the human imagination’, makes explicit the state of being that knows humanity is joined to divinity, which is why Job looks like the divine figure. For Blake, Jesus is not the saviour of a fallen race, but the resurrection and actualisation of the life that can embrace everything, even death, and never loses touch with the divine’s spirited exuberance.

Job looks up. He realises that this life is his life. He has left Ulro behind. He understands the seductions of Generation. He is stepping beyond Beulah, which might stare at the cosmos in passive wonder and gratitude. Job is on the threshold of being reborn and consciously, actively participating in the plentitude of life.

The scene can work on us by kindling of the inner shift that tips us towards comprehending Eternity. The angels call us with jubilation and song. They promise that we can know in ourselves that mortal life is the meeting place of heaven and earth. Our vocation is to join the finite and the infinite, outer and inner, the will and the imagination, the temporal and the eternal, because like death and life, one is the gateway to the other.

Sparkling Poetic Fancies

‘Tell me, what is the material world, and is it dead?’ Blake asks a fairy in the prologue to his poem, Europe: A Prophecy. The fairy laughs and sings:

I will write a book on leaves of flowers,

If you will feed me on love-thoughts, and give me now and then

A cup of sparkling poetic fancies; so, when I am tipsy,

I’ll sing to you to this soft lute, and show you all alive

The World, when every particle of dust breathes forth its joy.

The fairy loves fancies that glimpse other worlds. As J.R.R. Tolkien said: ‘Fantasy is a natural human activity. It certainly does not destroy or even insult Reason; and it does not blunt the appetite for, nor obscure the perception of, scientific veracity.’

Eternal perception, joyful dust, continual creativity, the resurrection of life and sparkling imagination comingle, Blake knew. Along with Tolkien and other writers, from Samuel Taylor Coleridge to Henry Corban, Blake was a passionate advocate for these qualities of true existence. They are not optional extras, surplus to living requirements, as if relics of the premodern age. Fantasy should not merely entertain. It is the heart of lives lived as human beings.

Death serves life. It expands single vision by opening eyes, annihilating the self that cannot see others, and presents itself as the awesome threshold over which it becomes possible to know the being that is the source of all lives. Gaining this sight is the crucial undertaking of our lives not only because we then see our destiny, but because when death does not brighten life, it threatens to destroy life; when death is denied or delayed, it deadens everything.

Blake realised that recovering the old wisdom about death is crucial in our times. It transforms us, not by changing our beliefs about what happens when we die, but by guiding us back to knowledge of the eternal life and divine light. ‘Awake! Awake O sleeper in the land of shadows, wake!’ he wrote at the beginning of his epic poem, Jerusalem: The Emanation of the Giant Albion. ‘I am in you and you in me, mutual in love divine.’ The sleep of Ulro can pass. Death can be experienced as the pathway to eternal life.