This piece was written for The Idler. To join me on the journey through the Inferno, Purgatorio and Paradiso click here.

The first group of the damned that Dante meets upon entering hell are running en masse “as an interminable train”. They can’t stop scampering and press together as an aimless collective.

Dante looks closer and sees that they’re following a banner. The flag is raised aloft as it rushes ahead of them. It can’t take a stand. It doesn’t know what it stands for. And that’s why its blind followers can’t stop either. They’re on a treadmill, running a rat race, forever.

This year, 2020, marks the 700th anniversary of the completion of the great Divine Comedy. It’s a miracle, quite as fresh today as when its final part, Paradiso, appeared in 1320, a year before Dante’s departure for the purgatory he anticipated. Unlike hell, that’s a place of hope, where people become all they are and capable of the tremendous vision of God.

The poem is many things: a diatribe against the church, a celebration of human qualities, a warning that this life matters, a path of awakening, an odyssey.

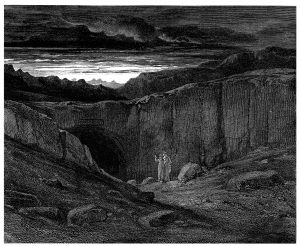

It was also born of a midlife crisis. Its opening words are famous: “Midway along the journey of our life / I woke to find myself in a dark wood.” (This is how Mark Musa translates it in the Penguin Classics edition, which I’d recommend both for accessibility and helpful notes.)

Dante presumed he’d been living his life well enough. He was a famous poet and respected politician. He appeared to be following the right path. But suddenly, he wakes up. He realises he has strayed, badly.

Though he’d not noticed, he’s wandering through a wilderness. He’s not sure what life is about and surrounding him, pressing in, are threats. The air tastes bitter. He becomes fearful. Truth is out of reach.

During his lifetime, his beloved city of Florence had collapsed into civil war. The conflict threatened his life and he was banished on pain of death. As it turned out, he was never again to see the gorgeous duomo, meandering Arno or handsome piazzas. It was a terrible burden to bear, particularly for a poet, because the city-states to which he fled spoke different dialects, held different festivals, sang different songs.

But his crisis was a turning point. It led to his greatest work that still speaks because his age was, in a way, the beginning of our age.

I realised this on the Idler retreat in Umbria last year. We visited Assisi, home of St Francis, whose revolution began to sweep across Europe a generation or so before Dante’s birth. It was a response to the bloated culture of the medieval church and to the mechanical ways of life that were spreading as mercantilism forced people into workshops. Francis stressed individual freedom and spiritual joy; a love of nature and care for others.

Dante celebrates these things in his poem. He sings of a cosmos that’s a festival not a machine. He sees enchanted gardens and mountains, magical rivers and processions. To read his poem is to realise how greatly human beings can flourish.

But it begins with the recognition of where he’s at, in a dark wood. He must descend into hell to understand the full extent of his predicament. Then he can begin the ascent to heaven.

It’s another reason why he can speak to us in 2020. The sense that something has gone wrong is now palpable. Mercantilism has morphed into hyper-capitalism. We can’t stop running after a flag that doesn’t take a stand. Life often feels bloated and mechanical. We’re in a spiritual crisis.

We must think again for ourselves. We must see the world afresh and understand. I believe Dante can help us discover how.