If Coronavirus turns Christian leaders into exemplary citizens, the gospel is lost

Will Covid-19 change our way of life, our politics, maybe even our civilisation? Personally, I doubt it. Business and political leaders are already charting a course back to familiar waters.

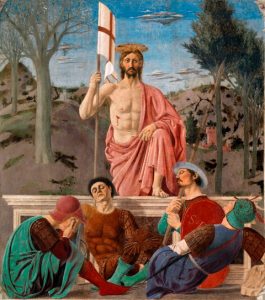

But Eastertime is a festival of novelty. It celebrates spiritual liberation not social success; eternal life not the prolongation of this life. It offers a different take. So, for a season, whether or not this world changes can be a secondary concern.

Let that go, and a fresh light dawns. It’s possible to realise that the effort to find happiness, the guilt at living wastefully, the frustration of powerlessness, brings us to our wits end. And that’s good. It’s a chance for something else. Visionaries have called it eternal life.

The insight is shared by great wisdom traditions alongside Christianity. But it’s become harder to see and trust nowadays because, in my view, those who might preserve the hope of it no longer have sight of it, in large part.

Preaching futility

The Archbishop of Canterbury’s Easter sermon this year is indicative. (Justin Welby gave advance warning of it on social media during Holy Week.) “We cannot be content to go back to what was before as if all is normal. There needs to be a resurrection of our common life,” he proclaimed, adding, “We have faith in life before death.”

The message sounds commendable, the words of a civic leader fulfilling his responsibilities. But it’s quietly disastrous. It turns bishops into exemplary citizens, not heralds of another country that’s already here.

It’s fairly futile, too. The archbishop feels he must inject hope into the Coronavirus crisis. As the pendulum of fear swings up, he believes the Christian task is to push it back the other way. But, of course, the upshot is that the pendulum keeps swinging. The dread of death that has become so horribly evident in recent weeks is perpetuated. The unconscious message is that there may be no way out. No wonder his gospel wanes.

What’s forgotten is that Jesus did not preach a better life, but the eruption of spiritual life, upon which humdrum existence depends anyway. He’s remembered as promising that what he knew of divine life would be known by others, too.

In fact, he said others would know it more so, were they to follow him and not adulate him. This is the end, as in aim, of the gospel he taught.

Eternity now

It’s the awareness of eternal life now. This is not about having hope for the future because there is no future in eternity. There is no past either. Instead, it’s the level of reality at which everything is always new, always verdant, always realised.

When Dante travels through the Inferno, in the Divine Comedy, he realises that one of the things that keeps souls in hell is their preoccupation with the past and the future. It distracts them from the present, which is the moment of change because it’s the only moment that’s real. And what a brilliantly light reality it turns out to be.

It comes like a thief in the night, Jesus remarked. It takes a cut with a subtle knife, an awakening, a release, a crack through which the light comes. It’s when the doors of perception are cleansed and everything is seen as it is: “infinite”, celebrated William Blake.

Only by daring to sense the truth of these perceptions is it possible to make sense of other things that Jesus said. “Be perfect!” “Take up your cross!” “Let the dead bury the dead!” “I came to bring a sword!” “Gouge out your offending eye!” “Sell your possessions!” “Hate your parents!”

Jesus’s injunctions are utterly incomprehensible to the gospel of amelioration, and probably offensive. They only begin to make sense when seen as attempts to catapult you into a different kind of life altogether.

Death is the path

That said, the really revolutionary part of Christianity is more disturbing still, though again, it is an insight shared with other great traditions. It says not that resurrection can inspire the masses, bring consolation or comfort, prove Jesus saves or that there’s an afterlife.

Rather, it’s that death is itself the path to life. Jesus, along with other geniuses like Socrates, realised that it’s only when death is encountered that it becomes possible to see it as a pivotal moment in life.

Death insists that we let go of what we’ve grasped and understood, because this is the crucial step to realising there’s much more that is always reliably there. It’s an awareness, perceived with intuitive eyes; a step into the timeless.

Death is the right word because, as the adepts also report, the paradox is that doing nothing and braving everything is the moment spiritual life reveals itself. In Daoism it’s called wu wei, in Buddhism emptiness, in Christianity the cross. It’s not inactivity or quietism. It is the hard task of giving up getting, and instead letting.

In psychotherapy, you see how the struggle to reach this point may take years and then, one day, it begins to happen. I think the awakening works like this because it’s only when you’ve seen who you are that the ego’s grip eases. Seeing is understanding, and that leaves you much less in thrall to your neuroses and delusions. They may or may not go, but they are deposed. As the teacher Jack Kornfield puts it, “You’ve got to be a someone before you can be a no-one.”

More life

It’s the release of death that those on their deathbeds report. It’s the realisation described by those who undergo Near Death Experiences, such as Elizabeth Krohn who was one day struck by lightning. “As I hovered over my body, I suddenly got it,” she writes in Changed In A Flash, a book that’s particularly interesting because it’s co-authored with the psychologist of religion, Jeffrey Kripal.

“I went from ‘Shit, my shoes are ruined’ to ‘I was so wrong about so much.’ It was an understanding that came to me instantly, suddenly, shockingly. I looked at my body on the ground and knew that whatever had just happened to me had given me an insight that the woman lying there could never have grasped on her own, even seconds earlier.”

Death is the gateway to more life. It’s a truth that shapes much of life in nature, from the seed dying to the summer turning, as well as in us, psychologically. Many people feel they don’t grow up until their parents die, because then they can take life and make something of it. Alternatively, it’s why life’s transitions are so poignant, from the child’s first day at school to the adult’s last day at work. They are little deaths. They enable further steps in life.

Death’s sting

Sleeping and waking echo dying and rising, too. I wonder how often insomnia is linked to a fear of death. But if you get used to the idea that many moments of most days follow that pattern, then death as the end of bodily life loses its charge and sting. It’s happened myriad times already.

“The now-moment in which God made the first man, and the now-moment in which the last man will disappear, and the now-moment in which I am speaking are all one in God, in whom there is only one now,” explained Meister Eckhart. He also realised that “My eye and God’s eye is one eye, and one sight, and one knowledge, and one love.”

The Coronavirus crisis may or may not prompt societies to change. It may or may not avert further disasters. I hope it does. But for now, there’s another hope to see. Our humanity is a road to divinity. It’s a road less travelled these days, but remains to be discovered.

So, Happy Easter! And I’ll give the last word to Jesus, in a typically punchy summary. “The one who loves his life will lose it, and he who hates his life in this world will keep it for eternal life.”