This article was written for The Idler.

The new William Blake exhibition at Tate Britain is tremendous. It features three hundred of his works, any of which on their own would command a room. Together they present an extraordinary energy.

It’s a rare chance to be immersed in the images of the prophet and poet, and could hardly be more timely as Britain convulses over the trauma of Brexit. Blake is arguably the greatest modern mystic these islands have produced. The show gives tangible form to his spiritual sight. I feel like we need it. But what is he telling us in 2019?

Blake is well known for being a commercial failure in life. One section of the new show reconstructs an exhibition that he put on in 1809 when he felt he might be recognised by his peers. It was a flop. He was shattered.

But I like to think that after the disappointment, he realised once more that his vocation was to live in the turbulent hell of London, supported by a few patrons and aided by his wife, Catherine. This was the crucible within which he must strive to bring heaven to earth; to manifest his vision in watercolour and ink.

He was in the right place because unlike the successful artists of his day, whom he decried as flatterers and sycophants, he was free. He could make the breathtaking illustrations of Dante’s Divine Comedy; the vivid plates to accompany Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress; his now most famous single work, Ancient of Days.

So his message is freedom and the vision it allows. But still, it’s a confusing communication because his freedom is so unlike the freedom that’s routinely pursued today.

Ask people now what liberty means and they might say freedom to determine your own laws or make your own choices. But Blake’s freedom is not at root the liberty to do this or that. It’s founded first on something more substantial: the glorious capacity to see “a World in a Grain of Sand”; “Heaven in a Wild Flower”. It’s a liberty based upon perception. “A fool sees not the same tree that a wise man sees,” he remarked.

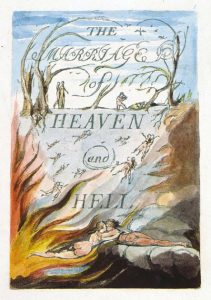

The doors of perception are cleansed by the sight that is found and fostered in the struggles of life. They put you between heaven and hell, innocence and experience, eternity and time, friendship and opposition, nature and the supernatural, vision and labour. He embraced this zone because contraries are liberating. They lift the mind. They refuse to leave you settled and still. Sometimes exhausting, it’s also thrilling.

Above all, such opposites facilitate the imagination. They power an ability to see through surface appearances. They glimpse the fuller reality of which the mundane world is a reflection or echo. “Attraction and repulsion, reason and energy, love and hate are necessary to human existence,” he explained.

His near contemporary and fellow romantic, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, called it “polarity”. He recognised that the dynamism of life arises out of the way things hold together when they are in the correct tension. Much as electricity is produced when a wire passes through a magnetic field strung between north and south, we are productive when we traverse the lines of force polarity creates. The trick is to learn how to be in the flow.

It’s for this reason that Blake railed against “single vision and Newton’s sleep”. He believed that the scientific worldview that was emerging in his day was losing sight of one pole of existence.

It would insist all is material, instead of material and spiritual. It would claim to have grasped nature in general laws, and lose touch with the infinite variety of her manifold instances. It would become so enamoured with its empirical measurements that it would deny the measureless, and so build “dark Satanic Mills” and bind people in “mind forged manacles”. He wasn’t wrong.

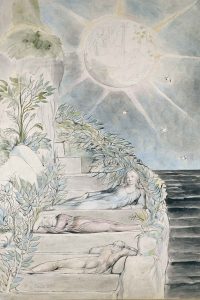

The Tate exhibition is a chance to feel the fuller energy. I’d advise ignoring the tendency amongst some critics to say Blake is unfathomable or incomprehensible. Rather, allow yourself just to dwell in the show.

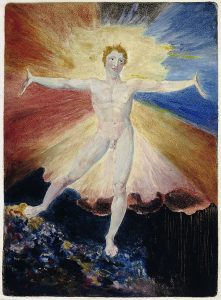

Enjoy the loveliness of his portrayal of a friendship. Feel the fear embodied in the figures bound in chains. Let your mind rise with angels as their feet leave the ground. Experience the agony of the traumatic moments from Biblical stories and myths. Feel his dark clouds, starry vistas, lithe figures.

Another Romantic writer, Owen Barfield, discovered how to access this life in poetry. He realised that the trick is not immediately to try to explain a poem but to let the words work on you. Let them speak as your imagination runs. There’s no right or wrong; no mere fantasy. Amplify any feelings and you discover that the words have soul. “I kept my attention on the experience itself and was not attracted by the rhetorical explanations which led away from it,” Barfield says.

What’s experienced is the inner power of the art. If it’s submitted to with fewer preconceptions, it can prepare the mind for new sights. The imagination is reignited. Feeling is charged. It’s this thrill that Blake brings and why he inspires. He offers a therapy for the soul that restores its capacity for vision.

That said, reason has a part, too. It can be bought into play when it has something to work with. Having made contact with reality afresh via the imagination, reason can sketch its maps and offer its links. It can serve to deepen, discern, direct.

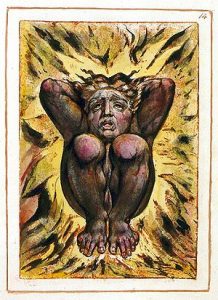

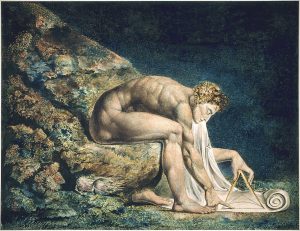

The point is that reasoning becomes unfree when it believes it is sovereign; when it forgets what Einstein caught in his remark about imagination being more important than knowledge: imagination is in touch with the world, whereas reason abstracts from it. The prison of reason alone is what Blake famously represents in his images of Urizen, Newton and the Ancient of Days. They assume that all they have is the measuring rod and compass.

The same mistake is made by the overbearing empiricism and reductionism of our times. The intellectuals who judge everything by logic and treat the cosmos as a machine have forgotten that they can only think because the world already contains intelligence. They can only understand because there is wisdom.

“There is no natural religion,” Blake proclaims in one of the books on display at Tate Britain. He means that spiritual life exceeds what can be captured by the natural sciences. It feeds the religious impulse because it spills in from the divine life in which our lives are embedded.

Blake believed he had a mission. It was to help his fellows regain spiritual sight. When feeling as well as reason, intuition as well as sensing, imagination as well as deduction are operative, it’s not actually that hard to find. Stay with the contraries. Stay with the images.

“I give you a golden thread, Only wind it into a ball, It will let you in at Heaven’s Gate Built in Jerusalem’s Wall,” Blake promised. This exhibition is a chance to take him up on it.