The new Idler magazine is out. Here’s my January 2022 thought…

New Years are much associated with luck. It’s why midnight is marked by rituals, from the explosive, such as igniting fireworks, to the convivial, in exchanges of good wishes. “Have a prosperous and healthy New Year!” Whether it’s with a bang or a blessing, the aim is to scare off the demons of misfortune and hope that haplessness is eclipsed by happiness in the months ahead.

It’s natural to do. The year is clearly turning. The days start perceptibly to grow longer. Time itself seems palpably to lean to the future. The impulse is to catalyse or impart momentum, energy, a fresh start.

Little wonder that the ancients felt the presence of gods at this time of year. Fortuna was one. A goddess of fertility, she was typically depicted blindfolded because she was felt to act randomly. Associated with whimsy and fickleness, she delivers “the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune”, as Shakespeare noted.

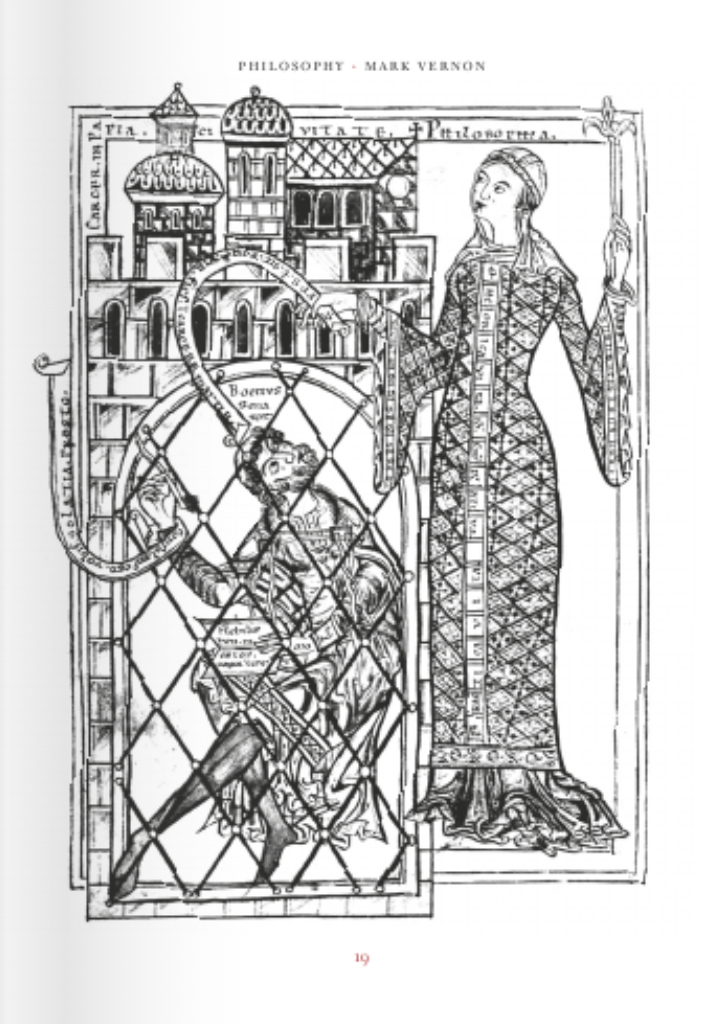

She also has a wheel, which she turns like time. We are to imagine ourselves strapped to it. When the going is good, we are on the upward swing, a rise. It’s a season when the cyclical nature of providence is easily forgotten. The foolish may even presume that their wealth or serendipity is deserved. They become entitled.

But if pride comes before a fall, so does privilege. The wheel has not stopped turning, any more than the sun stands still in the sky. It’s merely a high point and the way down is next. Fortuna’s wheel can as easily crush spirits as raise them, as effectively remove goods as bestow them.

The philosopher of late antiquity, Boethius (c480-524), called Fortuna deceitful and monstrous, and he had good reason to curse and despair. His book, The Consolation of Philosophy, addresses the ups and downs of life. It is a brilliant mix of dialogue, prose and poetry, and was hugely influential in the medieval period. If you seek a New Year’s resolution, reading it would be a good one.

Born into an aristocratic Roman family, he had a very good start. Even when his father died, leaving the young boy an orphan, his luck seemed plentiful. He was adopted by the leading Roman of the day, Symmachus, who had been a consul.

The collapse of the Western Roman Empire, another event in Boethius’s infancy, only produced more opportunities. He had a brilliant education, which included being able to speak fluent Greek. This made him invaluable as the various factions around the Mediterranean jostled for power. In his late twenties, Boethius was made a consul, and it didn’t stop there. Fortuna then seemed ready to pass the success onto his sons. By the time he was forty, they were invested with the consulship when barely out of their teens.

However, the wheel of fortune had not stopped turning and Boethius’s fall was shocking and sudden. In 523, still in his early forties, he found himself on the wrong side of a treason trial and was linked to the conspiracy. He was arrested, imprisoned, and a senatorial court condemned him to death.

Having had almost everything, he spent the last months of his life with nothing, in confinement, awaiting the day of his execution. According to one chronicler, this was carried out by a cord being twisted around his head, tightening until his eyes popped out. Then, the life was beaten from him with a club.

“I who with zest penned songs in happier days, Must now with grief embark on sombre lays,” he writes at the beginning of The Consolation of Philosophy (as translated by P.G. Walsh for Oxford World’s Classics). Fortuna’s presence no longer feels bright, but bitter. “Now she’s put on her clouded, treacherous gaze, My impious life spins out unwanted days,” he continues.

But all is not lost. Whilst in prison, Boethius is visited by another divine being, Lady Philosophy. During the course of his book, Boethius explains how she freed him from the slough of despond.

She administers medicine for the mind and, although kindly, the truths she imparts are potent and hard to swallow. She tells Boethius that she is used to life’s vicissitudes. They don’t affect her and needn’t worry him. Storms and human corruption may destroy all tawdry possessions, she explains, but there is a deeper realisation to have. What lasts and counts can never be removed. Fortune, favour and luck have nothing to do with the bestowal of what’s good, beautiful and true. Further, she adds, they are yours, they are everyone’s, from eternity.

At first, Boethius is resistant. He complains that he served what is good, beautiful and true in his life, so why must all he valued be so violently taken from him?

It takes him a long time to understand what Lady Philosophy seeks to impart. She is not offering shallow words of comfort or easy platitudes. Rather, she wants him to see through the changes and chances of this fleeting world to the calm centre within all things. She wants him to understand that, contrary to the old myths, Fortuna is not a random goddess. She is actually a shepherdess, drawing people back to the divine fold. This is why her greatest blessing can found in the midst of his apparently greatest loss.

He is facing death, yes. But he is also in a position to perceive that there are riches, glories and dignities that are not an accomplishment or asset, and so can never be diminished or damaged. “Whoever once shall see this shining light, will say the sun’s own rays are not so bright.” This is Lady Philosophy’s promise.

The Consolation of Philosophy was a bestseller because people recognised what he was talking about. In an age of insecurity, it’s acknowledged that life can turn sour in an hour. But such an age is also one in which to want more.

It will be nice if the New Year brings luck. It would be delightful if it enables the recollection of the boundless.