Mark Vernon chronicles a revolution in consciousness, published in Philosophy Now.

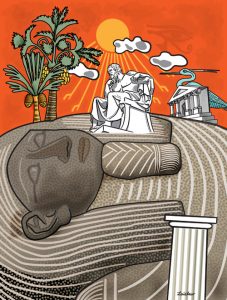

(Dust in the Wind, kenlaidlaw.com)

Why do we think of philosophy originating with the ancient Greeks? After all, it’s clear that the ancient Egyptians, who preceded Pythagoras and Plato, Parmenides and Aristotle, by 2,500 years, practiced wisdom too: “The power of Truth and Justice is that they prevail,” reports The Wisdom of Ptahhotep from around 2350 BCE.

In his History of Western Philosophy (1945), Bertrand Russell argued that it’s right to think of philosophy beginning in the sixth century BCE with the Greeks (in Miletus, a Greek colony in what is now Turkey), because it was only then that philosophers began to distinguish thought from theology. As is often the case in his entertaining volume, though, Russell was making a point rather than making a case. After all, the thinker who is called the first philosopher, Thales, is remembered for remarking, “All things are full of gods.”

In A New History of Western Philosophy (2004-7) the Oxford philosopher Anthony Kenny proposes that philosophy really begins with Aristotle (384-322 BCE), because Aristotle was the first philosopher to systematically summarize the teachings of his predecessors in order to criticize them. I think there is something in Kenny’s case, because to systematize is a new departure. It’s an approach that Aristotle’s great teacher, Plato, didn’t adopt.

We can gain a sense of the radical nature of Aristotle’s move if we consider some of the words he creates in order to make it. For example, Plato had the word ‘analogy’ but not the word ‘analysis’. The word ‘analysis’ was invented by Aristotle. This implies that, whereas Plato assumed that the purpose of argument was to point towards truth, Aristotle found that argument could break down the subject under study, much as dissection could cut up flowers and fish. Similarly, Plato had the word ‘quality’ but not the word ‘quantity’ – another word Aristotle coined. It’s why Plato is always more interested in oneness, twoness and threeness than one, two and three. His approach to mathematics is contemplative, as is indicated in his story about Socrates observing two raindrops colliding to form a single silvery ball of water. “Where did the twoness – the separation, the duality, the independence – go?” he has Socrates ask. But Aristotle is different. He can also contemplate numbers mathematically. He does argue that ‘3’ is a perfect number because it contains a beginning, middle and end; but he’s also interested in ‘how-muchness’ – which is what ‘quantity’ means. After this, thinkers became interested in the calculable aspect of objects in an empirical world. That’s something new. Owen Barfield writes that, with Aristotle, “The human mind had now begun to weigh and measure, to examine and compare; and that weighing and measuring has gone on – with intervals – for twenty-three centuries” (History in English Words, 1926, p.111). You could say that, after Aristotle, practical knowledge could be distinguished from theoretical knowledge. That’s different from the wisdom of myths and traditions, in which those two aspects are seamlessly intertwined.

It’s worth dwelling on just how profound this shift in thinking was. For millennia, our ancestors had felt they dwelt in a cosmos that was pervasively populated by living entities, and that these intelligences shaped how the world worked. When Ptahhotep wrote about Truth and Justice, he wasn’t thinking of abstract ideas as we do, he was thinking of personal characteristics of the god Maat. “Great is Maat!” his wisdom writing states. This is an act of divine praise. Truth and Justice prevail because Maat lives forever.

The evolutionary psychologist Robin Dunbar has been studying ancient mentality to think about the origins of religion. He has become fascinated by how hunter-gatherer groups engage in trance states, and has come to believe that in the Middle Paleolithic period, about 250,000 to 50,000 years ago or so, humans discovered that they could induce such altered states of consciousness. This discovery led to what he calls ‘immersive religion’, based on experiences of the spirits and beings that are revealed in visions and shamanistic practices. Communal dances and powerful rituals had the adaptive advantage of releasing endorphins that surged through the bodies of participants, which Dunbar believes proved invaluable. A by-product of such physical ecstasy is opioids, which would have eased the tensions that inevitably exist in large groups of people. Trance, therefore, not only led to perception of the gods, it greatly enhanced the sociality of humans. Whereas the communities of our primate cousins, such as chimps, are limited in size by the number of members that can be mutually socialized by grooming, this early religious experience meant that communities of humans could grow into tribes and, eventually, cities. In short, humans took an evolutionary path in which survival, stories, and a sense that the cosmos is enchanted, are intimately linked. To break those links was no mean feat, although it could be said that this is what philosophy achieved with its newfound analysis.

Aristotle didn’t change everything overnight himself, of course. In fact, I think he would have been amazed at how people read him now, as he himself experienced his practical and theoretical insights as divine revelations. This is why he advised his followers not to think as mortals, but to enjoy the way in which we share the life of immortals, when cultivating ‘the best thing in us’, which is our understanding. Aristotle’s ecstasy was to see how his mind could grasp cosmic wisdom through intuition and reason. However, in time it turned out that Aristotle’s innovations in the means of thought made possible a very different way of experiencing the world. What we now call the exact or empirical sciences are the offspring of his work. In our time, it has become possible to describe the world without reference to guardian spirits and transcendental intelligences at all.

Fundamental Changes in Thought

So Kenny is right, in a way: Aristotle was key to the development of what is specifically philosophy. However, my sense is that a prior move was also necessary. Something else had to happen before Aristotle’s revolution, which prepared the ground for people being able to appreciate the value of thinking in terms of quantities and analysis. This was another shift of consciousness – the birth of a mentality that was required to detect these aspects of reality, and make them stand out against the background flux of gods and living things.

The scale of this prior shift of consciousness can be perceived when if we ask what it takes to do what Aristotle did. He wrote on ‘ethics’, for the first time giving a systematic account of how to flourish. He described ‘logic’, the abstract rules that can guide thought. He derived ways of understanding the world that are not spontaneously found in nature by using ‘categories’, ‘species’, and ‘mechanics’. To do all this, he had to be able to take a step back mentally. He had to have an inkling of what Thomas Nagel famously called ‘the view from nowhere’. Only with such a detached, intellectual perspective could he have written ethics, logic, and all the rest. But this standpoint was not, in fact, his achievement. It was the achievement of his philosophical forebears.

Consider one of the Presocratic philosophers, Anaximenes (c.586-c.526 BCE). He is remembered now for his experiments. For example, he blew on his hand in two ways: first with his mouth open, then with his lips pursed. And he noticed something. When his mouth was open, the air felt warm; when his lips were pursed the air felt cooler.

What’s so interesting about the experiment is that countless people before Anaximenes had had the same experience. What makes Anaximenes different is that he paused, stood back in his mind from the experience, and asked that little question: Why? Why is there a difference? What’s going on?

Nowadays we’d say he’d stumbled across the basis for refrigeration: when gases expand, they cool, which is what happens when the lips are pursed. It’s called Boyle’s Law. But Anaximenes didn’t think to operationalize his discovery by taking out a patent and launching an industrial revolution. What Anaximenes was remembered for in antiquity was, rather, the shift of mindset evidenced by experimental curiosity. At the time, it was far more remarkable to point out that human beings could take a step back from their immersion in the flows of everyday experience.

Taking a step back was radical. Indeed, some people were alarmed by the suggestion. In time, philosophers were persecuted for asking their questions, leading to the execution of some, including Socrates. The problem was not just that philosophers challenged received wisdom: they disturbed people, too. That’s a much more unsettling challenge, though it’s one that in time can lead to revolutions of thought. Aristotle’s brilliance was that he could consummately ride the wave begun by the Presocratics. He paid the price for it, too, by being twice exiled from Athens.

However what was even more radical, was that by taking a step back from their experience, a person could discover their interiority : they could clearly distinguish their own thinking from the rest of the world. I think one can go so far as to say that for the first time in human history, there emerged people – philosophers – who strove to have their own thoughts. What these thinkers had done was invent the sense of being an individual.

Dunbar’s theory of the origins of religion can be used to flesh out this claim. After the discovery of the trance state, Dunbar believes, a second type of religiosity gradually emerged. It was based not on transcendent states of mind, but instead upon the everyday use of more humdrum rituals and rites. Pouring libations, saying prayers, sacrificing in shrines, visiting shamans and priests for charms and healing: these activities routinised religious experience and ways of life. Among other things, this meant that people did not have to go to the lengths of achieving altered states of consciousness in order to gain the social benefits of religion. Visiting spirit worlds and the ancestors could be reserved for festivals and feast days.

Dunbar calls this second type of religiosity ‘doctrinal religion’. He argues that it happened most clearly during the Neolithic Revolution (c.10,000-5,000 BCE), when our ancestors domesticated animals, began farming, and began living more settled lives. It’s when they also began building temples.

Ancient Egypt was one of the greatest manifestations of this way of life. Its legacy of great pyramids and funerary art can still astonish us today. It speaks of the second phase. In this phase, the god Ra could be felt to have won the eternal struggle against the god Apophis every time the sun rose in the morning.

Individuality Through Philosophy & Religion

Returning to how philosophy relates to these developments, I suspect that Plato learnt about the ancient Egyptian way of thinking, after Socrates was executed in 399 BCE. Plato’s interest in Egyptian religiosity is captured in later dialogues, such as the Timaeus, where he describes Egyptian priestly rituals and temple rites as becoming mechanical and ossified. I guess he visited regions of the Nile, participated in the mysteries, and found them wanting. They didn’t connect him to Ra and the other gods.

His diagnosis of the failure was that a new consciousness was emerging – that of the individual. He’d felt this supremely in the questioning of Socrates. Socrates was the personification of the new individual, and it cost him his life. The ‘gadfly of Athens’, as Socrates was called, irritated people so profoundly because he had made asking ‘Why?’ and ‘What does this mean?’ a way of life. He was tried for treason and found guilty because he was perceived to have withdrawn from the collective way of life of his fellow citizens: part of the charge against him was ‘the introduction of foreign gods’. And rather than participating in collective religion, Socrates had a personal vocation – a private connection to the god Apollo. As Plato has him say in the Apology : “This is what has prevented me from taking part in public affairs, and I think it was quite right to prevent me.”

This refined sense of individuality was ripe for Aristotle. He could extend the innovative approaches to life it makes possible, captured in his neologisms and philosophical works. Put it like this: if you want to know why Aristotle was subsequently so important to European thinkers for the next two millennia, one answer is that his work crystallised and empowered consciousness.

New types of consciousness are not born every day. They also take time to sprout and flourish. This is what happened through the emergence of ancient Greek philosophy. The type of mentality that we can relate to, based upon individuality, came to the fore from the sixth to the fourth centuries BCE in Greece. And philosophy as we know it was born with the creation of the individual.

That said, I don’t think this new consciousness immediately became widespread with Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle. But the most popular of the Hellenistic schools in the centuries that followed, the Stoics, did much to spread it. They developed techniques that strengthened the sense of individuality when they noticed that it had therapeutic benefit. They were practices of self-examination, self-awareness, and self-expression that developed self-knowledge of personal errors and weaknesses, virtues and strengths. The aim was to secure an interior equanimity. The historian of ancient philosophy, Pierre Hadot (1922-2010), called these techniques ‘spiritual exercises’ because they worked at the level of the interior life of the individual: “Spiritual exercises almost always correspond to the movement by which the ‘I’ concentrates itself upon itself and discovers that it is not what it had thought,” he explains in What is Ancient Philosophy? (1995, p.190).

The new sense of being an individual became widespread after the birth of Christianity. Following thinkers such as Owen Barfield, I’ve come to believe that the democratization of individuality was a major reason that Christianity became so popular in the early centuries of the first millennium CE.

Christians believe that Jesus was both fully human and fully divine, and that his message was for all people to personally accept. This idea transformed individuality from being a philosophical achievement to being an ideal for all humanity.

Once more, evidence for this shift can be found in the new words that pop up. For example, in the second century, the early Christian apologist Justin Martyr described for the first time what it is to have ‘free will’ with a sense that we would recognise – that of personal agency. Alternatively, the first person is accused of ‘plagiarism’ at about the same time, because for the first time it was possible to worry about authorship, since the individual who wrote a text now mattered. Christians also started fraternising with one another not because they belonged to the same families or cities, as was standard in the ancient world, but on the basis of personal conversion and commitment to the new faith. They could connect as individuals, rather than as relatives or citizens, and this is why Christianity spread. “Christianity’s sharpest advantage was its inexhaustible ability to forge kinship-like networks among perfect strangers,” writes the historian Kyle Harper in The Fate of Rome (p.156, 2017).

Their consciousness was like ours, in that it had individuality. But it was not the same as ours because, through late antiquity and the medieval period, individuals still felt themselves to be connected to nature, the cosmos, and God. They no longer felt that they were being swept along by the god of fate and other spirits; rather, they felt that if they lived virtuous lives their individuality could reflect the life of God. However, nowadays consciousness has shifted again, and it’s become possible to doubt that reciprocity, even doubt the existence of deities or spirits. We can become isolated individuals alienated from the world around us, which it’s possible to regard as having no inner life at all.

Even so, we can still read Plato, Aristotle and the Hellenistic philosophers and find they illuminate our lives to a degree, because, in certain ways, we still share their consciousness. When we learn about Socrates’ life and death, we are learning about what it took for individuality to be born. There’s a sense that his sacrifice is what it took for our type of experience of life to emerge. We admire him. He seems not like a traitor but a hero. This is why we think of philosophy as originating with the ancient Greeks.