This article was published in The Tablet.

I was once in a discussion about mission. We were a sub-committee, mulling over what we should do to spread the gospel and boost church numbers. An hour passed, as did various moods, from anxiety to optimism. And then someone said, “But wait. It’s not our mission that matters. It’s God’s mission.”

The thought fell on me like a revelation. We had got the question wrong. What we should be asking is, where is God’s mission happening?

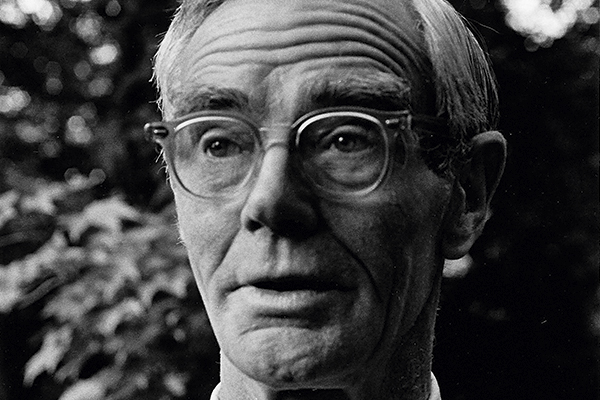

It was only with reading Owen Barfield that I began to gain a proper sense of how to find out, as well as grasp what might be unfolding in our times of church decline. He was a lesser known member of the Oxford Inkling group, though the one whom C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien said had the most penetrating ideas.

Born in 1898, when Queen Victoria was on the throne, he died in 1997, a few months after Tony Blair became prime minister. He saw one world die and another world born, and also witnessed the two world wars that erupted in between.

He faced periods of acute depression, too, and major disruptions in his career. Unlike Lewis and Tolkien, he was never employed by Oxford University, though at first, it looked as if he would be the first of the Inklings to become famous. In 1925, he published a mythopoetic story for children, The Silver Trumpet, over a decade before The Hobbit, and his first non-fiction book of lasting significance, Poetic Diction, came out in 1928.

He gathered supporters from the start. W.H. Auden wrote a forward for another early book saying it should be “required reading in all schools.” But the early promise failed to produce sustained academic employment with the upshot that he spent most of his working life with the family law firm in London. Long decades passed until 1957, when his magnum opus, Saving the Appearances, was published. Then, when Lewis died in 1963, he embarked on lecture tours in America to talk about his “oppositional friend”, and the transformative nature of his own ideas began to spread. The Nobel Laureate, Saul Bellow, noted that Barfield’s aim is not just to be interesting but is “to set us free.” The Franciscan writer, Richard Rohr, describes Barfield as “a paradigm-busting Christian thinker”.

The radicality was discovered when, aged 21, he recovered from a bout of depression. He felt that he had been cured of a disease of the soul. Although it could threaten to return, and further had spread like a miasma throughout the modern world, the experience was a kind of spiritual awakening. He had found a way out of the existential catastrophe Nietzsche called “the death of god”. It never let him down.

Two things happened. First, he fell in love with the woman who would become his wife. Love may be the painful realisation that someone else exists, as Iris Murdoch, another Oxford philosopher and writer was to remark, but he no longer felt alone. And that was not all.

He also fell in love with poetry, and it was this love that took him further. He noticed that poetic words are powerful, even magical. They are a source of delight because their resonance, vigour and colour channel worlds of experience that, in his depression, he doubted were there. Like a shaft of sunlight on a cloudy day, they illuminate what he came to call “the inside of the whole world”.

The awakening did not stop with that but led to his big idea: words have soul, an inner vitality that, when embraced, is transformative. They reveal a storehouse of treasures that is permanent and keeps giving. They echo the activity of the divine Word at work in the cosmos.

The idea is close to that of Tolkien’s theory of “subcreation”. Indeed, Barfield contributed directly to Tolkien’s formulation. This is the insight that imagination is “a higher form of Art” because it brings worlds into being. Words channel reality; they wake us up to it. This soulfulness is felt when a successful novel, like The Lord of the Rings, is experienced not as telling you about another world. Rather, it’s experienced as being another world.

Barfield pursued the revelation further. If words have soul, he continued, then they can also tell us about the human minds who deploy them. In particular, they can tell us about how worlds change because it’s clear that words change meaning over the course of time. They are “fossils of consciousness” and the fossils reveal a pattern.

To simplify slightly, Barfield discovered that in earlier times, words tended to carry meanings which spoke of outer and inner realities that are woven together. Then, in more recent times, the use of words shows that these two dimensions of existence have tended to split apart.

Take a case central to Christianity, the Greek word, pneuma. For example, in modern translation, John 3:8 reads: “The wind [pneuma] blows where it chooses, and you hear the sound of it, but do not know where it comes from or where it goes. So it is with everyone who is born of Spirit [pneuma].” Two different words for pneuma are used in English that represent what we assume to be separate spheres of reality. “Wind” is an external, tangible phenomenon. “Spirit” is internal, intangible. But the writer of these verses did not have to make a distinction and turn one into a metaphor for the other. “Wind” and “Spirit” were two aspects of a continuous experience: pneuma.

The same pattern repeats time and again in language. Over the course of his long life, Barfield was occasionally presented with supposed counterexamples, though they all proved false alarms. So what does the pattern mean? It reveals how worlds change.

The separation of the inner from the outer meanings of words represents a splitting in the human psyche. It can be put like this. Our ancestors must have felt themselves to have been part and parcel of a flow of life that moved in, through and around them as easily as the wind-spirit moved amongst the trees. Barfield called it “original participation”.

One place it’s remembered is in Biblical stories such as that of Adam and Eve walking with God in the Garden. Before the Fall, they weren’t ashamed, which is to say, they weren’t aware of their separation from God and each other. But then comes the Fall. It rehearses a shift.

“It’s a story that remembers an increase in human beings ability to differentiate between things, such as good and evil, mortals and immortals,” explains Fraser Watts, the psychologist of religion, speaking about Barfield at a recent meeting of the International Society for Science and Religion. “But that differentiation comes at the cost of being able to integrate things.”

The immersive experience of life is lost, with the upshot that nowadays, we tend to feel that we are cut off from others, nature, the cosmos and God. Barfield called it a “withdrawal of participation”. But it’s not the end of the story.

A crucial detail in Barfield’s idea is that the withdrawal has meaning. It isolates people but it also fosters a sense of interiority and autonomy. That’s why the Genesis myth contains details such as Adam blaming Eve and Eve blaming the serpent. They have become defensive, they struggle, but you could also say that these are the signs they have become human beings with an independent subjectivity. They might also, therefore, discover new kinds of freedom.

In other words, the shift is also a gift, which brings us to the meaning of Jesus. He shared this tricky I-consciousness. But what he showed in his life is that human interiority, reflected in our capacity to say “I am”, can be the perfect receptacle for the divine I AM. A new state of being is possible: to own our humanity and to be fully transparent to God. We catch a glimpse of it when poetic words light up our inner life because in that moment we become actively transparent to the inner life of the world around us. It’s a moment when the Word becomes incarnate in us because we say, “yes”.

Such awareness comes on the other side of the withdrawal of participation because it’s only then that a possessed sense of interiority can form. Separation is a necessary stage.

It’s why the cross became the central Christian image, along with Jesus’s cry: “My God, my God! Why have you forsaken me?” Such “scenes of solitariness”, as the philosopher A.N. Whitehead called them, are the central moment in any spiritual journey of weight and have subsequently been given many names from the dark night of the soul to having a breakdown. It’s a crisis that makes for a turning point.

A new kind of participation becomes possible, which Barfield called “reciprocal” and “final”. His spiritual awakening, fleshed out by his study of words, led him to a fresh account of the meaning of Christianity. Humankind has undergone an alienation from God that enables the return of a freer humanity to God. Felix culpa! Happy fall! It was Augustine’s discovery when he realized God as “more in me than I am in me,” and that God was “waiting within me while I went outside me.”

Mystics offer us a foretaste of it when they realise that their life mirrors divine life. “Our task now is to participate with an expanded sense of reality and learn to talk about it,” Watts adds.

I believe it was a parallel insight that led Karl Rahner to make his well-known remark, “The Christian of the future will be a mystic or he will not exist at all.” This is how to embrace our moment in history, which values the individual like none before. Education has become a universal goal. People are equal before the law. Everyone – women and men – have a vote. It is also a time that is stressed and conflictual, frequently deadly. But God is at work in this fall. In ways we don’t always understand, when we too can feel forsaken, a receptable of divine light and life is forged.

When looking out for God’s mission now, I seek signs of spiritual crisis, deepening interiority, renewed delight in nature, and articulate mysticism. Barfield is my guide.