The debate about the differences, if any, between gay and straight relationships is a tricky one to conduct as it is so intertwined with feelings about the Christian legacy in a secular world. So perhaps we can take a step back, to a time before the secular, to a time before Christianity, and see what resources we find in Plato.

His dialogue the Symposium is provocative. Perhaps the best known bit is Aristophanes’ speech, in which the ancient Greek comic describes humans as originally being wholes who were cut in two by Zeus. That ‘explains’ why we spend our lives looking for our lost halves.

Interestingly, Aristophanes describes three kinds of aboriginal whole – the hermaphrodite male/female and two kinds of homosexual whole, that after the divine surgery were split into two men and two women respectively. Hence he has a mythical etiology for homosexuality as well as heterosexuality. What might that contribute to the current debate?

Well, it suggests that whilst all humans seek union with the person they come to think of as their other half, they seek differently. Many seek a contrasexual half. Some seek a same-sex half. So within a common quest, there’s important variance.

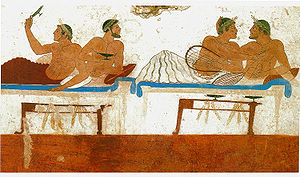

Just what that variance might mean, beyond the obvious purely sexual difference, is itself explored in another speech, that of Pausanius. Pausanius – who is, incidentally, in a long-term relationship with another guest at the symposium, Agathon – argues that there are two kinds of love. One is the child of Pandemos Aphrodite, pandemos meaning ‘common’, as in ‘usual’. The other is the child of Urania Aphrodite, urania meaning ‘of Uranus’, the god of heaven.

The significance of this distinction emerges via a little Greek mythology. Pandemos Aphrodite is herself the child of Zeus, which is to say she is a goddess who appeared in the time of the generation of gods. Urania Aphrodite, as the child of Uranus, belongs to the archaic period before then. So the love that Pandemos Aphrodite inspires is itself generative, mostly obviously aspiring to have children. The love that Urania Aphrodite inspires is not, but rather is primarily interested in a certain kind of friendship between the lovers – one a bit like that shared by Pausanius and Agathon in fact. Its ‘offspring’ will not be children but the enrichment of the couple and humanity in other ways – not least in poetry: Agathon is a prize-winning poet, the celebration of which is the reason for the symposium Plato recalls.

So a difference opens up. Heterosexual love will be capable of both generative love and heavenly love, as indeed Socrates seems to have been: he was married and had children, but his philosophical life was inspired by the love of Diotima the priestess, who appears later in the Symposium. Homosexual love will not produce children with its consummation – reproductive technologies notwithstanding – but will instead tend to focus on a different telos to ensure it grows, that being a kind of erotic friendship. Plato explores what this can nurture later in the Symposium when he describes the ladder of love that Diotima reveals to Socrates.

Both loves are demanding, though there is one feature of heavenly love that seems salient. According to Plato, such love must sublimate its early sexual passions in order to channel its energy towards ‘higher things’. Plato describes this in the Phaedrus, and in the Laws actually bans homosexual sex as too likely to fail to reach that sublimation, as a result of becoming trapped in love of a destructively lustful kind.

All in all, Plato does not offer a blueprint for the differences between straight and gay love – and their similarities. Human psychology is too complex for that. But he does have a variety of myths and reflections that might help to think things through.