This year, 2020, marks the 700-year anniversary of the completion of the great Divine Comedy. The final part of Dante’s masterpiece, Paradiso, appeared the year before he died, in 1321. The poem is many things: a celebration of human qualities; a warning that this life matters; a path of awakening; an odyssey; a diatribe against the church of his day. But it was born of a crisis. Dante begins his journey by waking up in a dark wood. The air tastes bitter. He grows fearful. The way forward seems firmly blocked.

His predicament resonates with where we find ourselves now, in the middle of various emergencies, with a spiritual crisis underlying them all. Individually and collectively, we must see the world afresh and find ways to re-orientate ourselves. Alongside other divinely inspired texts, I believe Dante can help us discover how. In this piece, I want to pick one strand in the golden thread of Dante’s vision: the role of erotic love.

It is the type of love that tends to be viewed warily in monotheistic religions, particularly in their institutional forms. They are more comfortable when love manifests in other guises, like agape or friendship. Christianity provides an obvious case in point. Punitive attitudes towards eros set in from its earliest days, explains the historian of late antiquity, Kyle Harper, in his brilliant book, From Shame To Sin. For example, Saint Paul felt that sex provided a test case for how the new freedom to be found in Christ differed from the old freedoms of Roman citizenship. For the Roman freeman, a key demonstration of liberty was doing what you willed sexually with your and others’ bodies. But Paul preached a different liberty. It was not civic but spiritual, known through belonging to Christ. Sexual acts, of any sort, were therefore interpreted as an implicit rejection of divine grace.

“I wish that all of you were as I am,” he writes to the Corinthians, which is to say, celibate. As Saint Augustine was later to teach, the one thing that erotic love reveals to us is that its surges of desire spring directly from humanity’s rebellion against God. At best, it is what you might call a necessary evil.

Eros as daemon

What is striking is that these worries and prohibitions stand in marked contrast with the attitudes towards eros found in mystical and visionary traditions. These tend to take a very different view, in the West reaching back to Plato. He taught that Eros is a go-between spirit or dynamic, known in the ancient world as a daimon, whose embrace widens and deepens perception. In the Symposium, he tells of how the priestess and prophet, Diotima, taught Socrates that the ‘arts of love’ can lead to the highest mysteries of sight, ultimately catching glimpses of what’s good, beautiful and true.

Dante clearly felt a tension between the two attitudes towards eros in his life. His early poems describe the agony of controlling sexual impulses. His muse was, of course, the young lady, Beatrice. Her image utterly, almost ruthlessly, seized his imagination. He reached a pivotal moment in his spiritual and poetic struggle when he realised that exulting the beauty he saw in her could be an end in itself. He gradually found a way of harmonising the love she inspired in him with the ascent of the soul to the divine.

It required a combination of eros and logos, meaning the intelligence or insight that can discern the presence of God. This is because the divine image itself can be known as a combination of eros and logos. “Beatrice is Dante’s pole star for finding his way through love’s vicissitudes, in his search for what is constant and eternal in love and desire”, maintained Andrew Frisardi in his recent series of lectures at the Temenos Academy.

In short, the right use of eros is at the heart of Dante’s message and he presents a key moment of realisation during Canto 9 of Purgatorio.

Violent dreams

The moment comes after Dante and Virgil have emerged from the subterranean darkness of hell. The first part of The Divine Comedy, Inferno, relates how their journey begins with a descent into it. They witness the numerous ways in which human beings can become trapped by their desires. It is a crucial part of the journey for Dante because, when meeting these souls, Dante simultaneously encounters the darker parts of himself. Seeing the extent of these shadows is also to begin to open up to how they may be transformed.

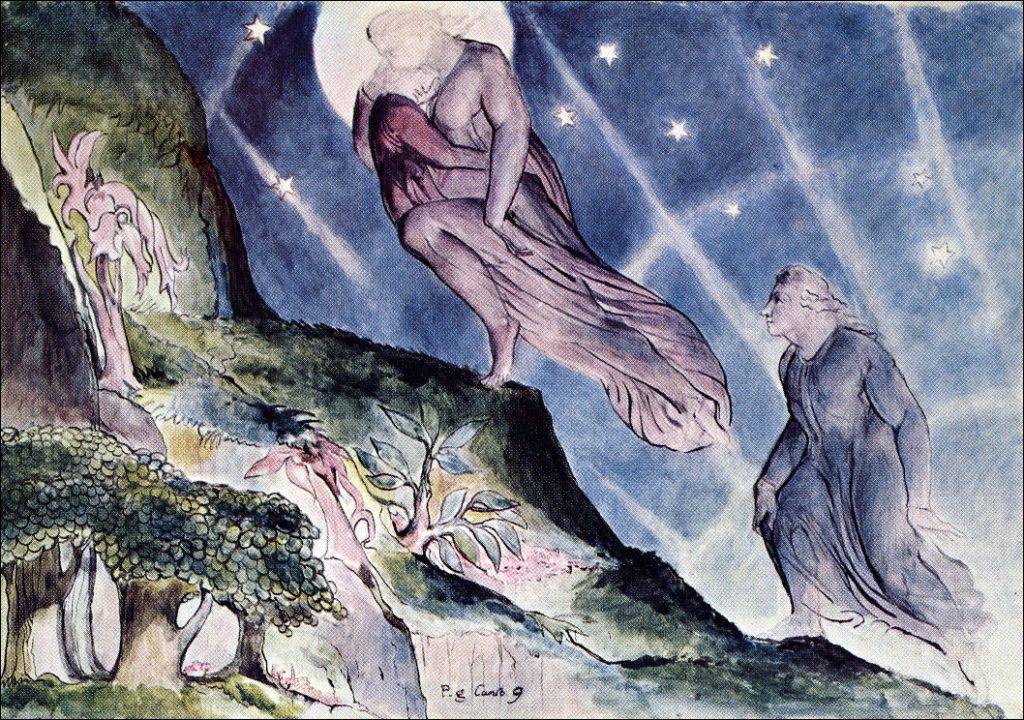

This is what begins to happen on Mount Purgatory, in the second part of The Divine Comedy. The setting of Canto 9 is the end of the first day of ascending the mountain. During the day, Dante has been finding his bearings in the second domain of his pilgrimage. Exhausted, he now falls asleep and as he sleeps, he dreams.

He dreams that he is snatched from the mountain by an eagle. It carries him into the high heavens, much as Jove abducted Ganymede, lifting him into a burning fire. In Mark Musa’s translation:

I saw him circle for a while,

then terrible as lightning, he struck down,

swooping me up, up to the sphere of fire.

Then, Dante wakes with a jolt. He is dazed, “feeling the freezing grip of fright”. It takes some comforting words from Virgil to calm him down, and what Virgil tells him is a revelation. In fact, his guide explains, whilst he slept, a lady from heaven appeared. She is Lucia and, as the day’s climb had been hard going for Dante, she had carried him a little further up the mountain. She told Virgil that she wanted to “speed him on his journey up”.

Much ink has been spilled over the meaning of the dream, but it is pretty clear that the dream and what happened whilst he slept are in stark contrast. The dream was a nightmare of barely disguised sexual violence, an insight that is underlined by several allusions to uncontained lust that Dante makes in other parts of Canto 9. The reality, whilst he slept, is of love coming to his aid.

Lucia is significant because she is one of three beautiful souls who keep a benign eye on Dante from the celestial heights. The other two are Beatrice and the Virgin Mary, and note: he has not one but three beautiful ladies loving him. This is one indicator of how eros’ passion is transformed. What might be judged almost as a kind of promiscuity becomes an excessive desire and power to help.

As to the dream, I think what it implies is something like this. If inwardly, Dante had experienced the outward actions of Lucia as a kidnap, almost a rape, as he awakens he realises how profoundly mistaken he is. She was actually speeding him on his journey towards divine love.

The implication is that the transformation of eros from its dark manifestations to its true character requires him to work on his perceptions. He must hold in mind both images – one of violent and lustful snatching, the other of divine embrace and carriage. In so doing, the possessive character of eros that currently dominates his mind is revealed by the dream, and it might give way to the dominant character of divine love, which is of dynamic participation. As it is summarised by the famous last line of Paradiso, this is “the love that moves the sun and other stars.”

Using Eros

The shift is key to Dante’s transformational erotic spirituality, and it seems to be confirmed by what happens next in Canto 9. It turns out that Lucia has carried Dante, with Virgil walking alongside, to a gateway. It marks the start of purgatory proper, which Dante is now ready to enter, having oriented himself and gained a first taste of the dramatic changes in him that the ascent will demand. Dante sees that the gateway can be entered by ascending three steps. The first looks like glass; the second like cracked pumice; the third like flaming blood spurting from a vein.

The steps are usually interpreted allegorically by commentators, but I feel a more natural and penetrating way to explain them arises from the experience he has just had. He sees his image in the first step of glass, much as he has seen an aspect of himself in the dream. This is represented in the second step, which he is now able to step onto because he can tolerate the cracked and troubling erotic impulses inside him. And because that disturbance is born, a third step up becomes possible, when this flaming passion, now in the process of being changed, can bear him to a threshold.

You might say that the dream, the carriage and the gateway are an initiation. Dante still has a long way to go and his erotic desires will require further work. As he follows the path, he learns much more about how his ambivalence about eros has to do with human ignorance and youthful experience, as well as the painful struggle to align his desires, his perceptions, his knowledge and his will so that he can become capable of paradise.

But Canto 9 conveys a central element: that which seems monstrous, feels dark, frightening, possessive, wild – like an uncontrolled rape of life itself – is something remarkably different. If we can bear ourselves, and allow ourselves to be borne, then we will become able to enjoy a free, indulgent and delightful participation with what is beautiful, good and true. Eros can be transformed, not condemned. It is a love to befriend, not reject. It can energise our steps up Mount Purgatory and then our flight into paradise.

Dante said that he wrote for the benefit of a world which lives badly, not least in its poor use of the divine gift of erotic love. Contemplating each step of his journey might foster the transformation of our own mixed passions. It offers a pathway to liberty, which speaks as profoundly now as it did 700 years ago because Dante charts how the arts of love can foster the highest mysteries of sight.

My canto by canto commentary on the Divine Comedy can be found on my website, Buzzsprout and YouTube.