In time, a different sense of life emerged. It came in a new phase of the development of consciousness. To stories and myths was added literature and abstract thought, then the detached meaning of words and, with that, finally, the inwardness of individuality.

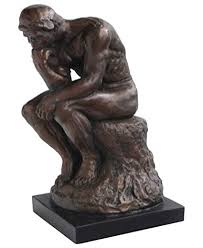

It brought the self-awareness that is familiar to us, of a mental space within which essentially private thoughts and experiences autonomously rise and fall.

It’s the dominant sense of being human now. There is what’s me and what’s not me. What’s mortal seems separate from what’s immortal, as does my inner life from the life of the cosmos – to the extent that it’s routinely possible to doubt both the life of the cosmos and of immortal life.

God has died, as Nietzsche observed, and we have killed him.

In this absence, we readily feel ourselves to be specks of encapsulated sentience lost in deserts of mechanistic expanse. Or worse. Neuroscience can make people suspect that they don’t have an inner life at all, as if their thoughts and feelings were nothing but firing neurons and surging hormones.

As the neuroscientist and historian of ideas, Iain McGilchrist, points out, we need constantly reminding that whilst the brain does indeed light up when we eat a cheese sandwich, a brain doesn’t taste cheese. We do.

Barfield called this experience a “withdrawal of participation”. It is the period during which early quasi-scientific ideas about the cosmos were formed. Humans turned somewhat away from old myths, as they started to seek not to share in nature but to explain the constants of nature. For the first time, they had to ask about the meaning of life because its meaning no longer spontaneously revealed itself to them. People could become cut-off, alienated.

But with the withdrawal of participation came an astonishing gain too. The concentration of inner life that separation brought came hand in hand with an intensification of the sense of being an individual. And with that came all manner of novel possibilities.

Moral responsibility emerges, as do new relationships with deities. For example, our ancestors started questioning their fate, as if it were maybe not deemed by the gods, and instead pit their wills against blind fortune and formed complaints against divine injustice.